Support these articles

Show a little love for independent writing (mine!). In return, I promise eternal gratitude and premium content that's suitably opinionated for a dedicated audience.

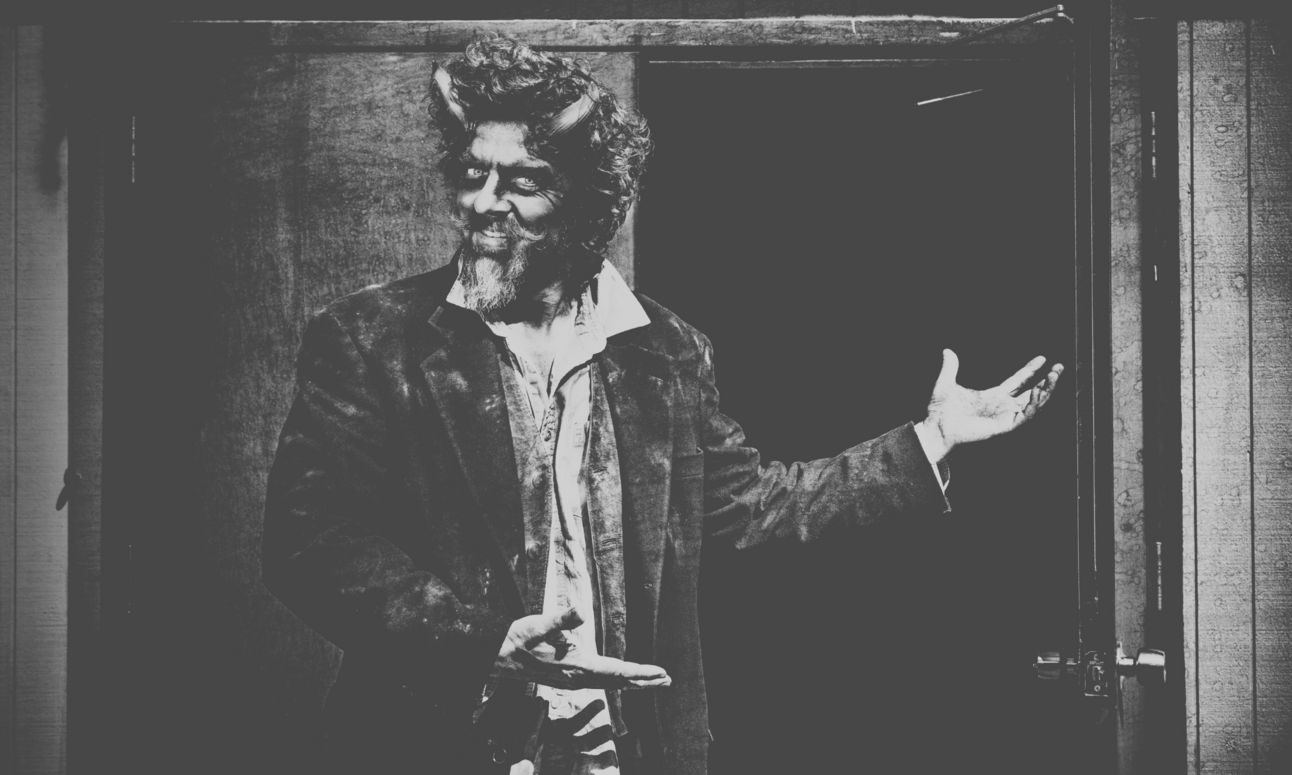

In English-speaking parts of the Commonwealth — at least, the parts that play cricket (join us, Canada!) — the true Queen lives. Kylie Minogue, long may she reign, released a banger of a pop tune called Better The Devil You Know in 1990. It cemented her superstardom and was inspired by her relationship with fellow Australian splurge-bomb, Michael Hutchence. I mention these two icons of carnal desire for good reason — I want to talk about Thomas Edison.

In my view, Edison is the personification of the modern world's birth. Consider that there have been three great energy revolutions. Fire came first, naturally, and people learned that energy released as heat could be used for all sorts of useful things. Cooking and making metal tools are happy examples, creating sharp and pointy things to put on the end of sticks was less jolly.

After that came steam, which enabled the energy from heat to be transported a short distance as mechanical energy. Not far, just a stone's throw, but far enough to power machinery and pistons. This was so revolutionary that the first industrialized island became the most powerful geopolitical entity ever known.

But in the late 19th century, Britain failed to harness electricity like Edison did in America. This is despite the Britishness of the century's two great electric minds, Michael Faraday and James Clerk Maxwell. In fact, keep naming the other great minds that contributed to electricity — Gauss, Ampère, Ørsted, Volta, Joule, Ohm, Tesla — and you'll notice that they're all European. But where Europe did the thinking and wrote the equations, it was America that saw its industry really run with the idea. The energy from heat could now be transported great distances and be used to in ever more intricate tasks, many of which we still haven't imagined.

Here's the thing — America was a second-rate power when Edison founded his Electric Light Company in 1878, and was still considered a second-rate power by the global elite when he died in 1931. In the intervening years, America had developed the DC motor, powered flight, the assembly line, mass-manufacturing, air conditioning, it’s GDP had outpaced that of the British Empire, and the collapse of its investment markets had triggered a global meltdown.

Yet, despite the obviousness of America's innovations and economic impact, it was seen as the little brother when compared to its European peers. Even after The Second World War — when America emerged as the only nuclear-armed nation and the Bretton Woods System declared that its economy was the hub of everything — it still took until the 1950s for the US Dollar to eclipse the British Pound as the largest global reserve currency.

My question is simple. Did The United States become the West's leading power closer to the 1950s, or the 1880s? It's a hard question. Great civilizations tend to peak and decline slowly and it's difficult to see where things went wrong. Britain and Europe appear to have peaked and then quickly collapsed into catastrophic war in the mid twentieth century. Unless, of course, you also consider the atrocious war in that broke out twenty-five years earlier.

You can't miss it, really. The First World War was so horrific that popular hubris thought no such thing could ever happen again. Yet, in its aftermath, Europe quickly rose from the ashes; Britain, France, and Italy expanded their empires; Germany ramped up military production; and revolutionary Russia stabilized. Why would the world, so recently in flame, return to a status quo with heavily armed, imperialist and fractious Europe at the top, instead of relatively unscathed America?

No doubt, there are complex and multifaceted reasons to chew over. I suggest something simple — better the devil you know. Maybe it was just easier for the world to pretend it was 1913 again, and that the war was an aberration in a stable order? And perhaps that stability rested on the fiction that Europe was the place that really mattered, even though many of the biggest things had clearly been happening in America for quite some time?

Segue to now, and it's tempting to ask if our grandchildren will look at Trump 2.0 as the moment the American Century ended, or the moment we were forced to realize that it already had? Granted, there are Edison-like factors. For instance, I wrote a while back that although America is the ostensible hub of global technology, its root-and-stem has long been Chinese materials and Dutch/Taiwanese manufacturing. There are even the beginnings of a capital and talent flow away from America and towards Europe and China. (Scott Galloway has two excellent articles on this - The Great Rotation and Brain Drain).

But that doesn't necessarily signal a sea change in history. America didn't rise to prominence through a zero-sum game of international competition, but by stitching together a new world based on collaboration. That world allowed Europe to build peace and prosperity, lifted more people out of poverty than anyone in 1945 would have believed possible, and still has America as its linchpin.

Yes, wealth and power are dispersing to the point that Washington will lose the option to rule the world by coercion, but that option has never really been exercised anyway. There have been American wars and military adventures — I’m not scrubbing out Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, or dozens of bombing campaigns — but there has been a lot more in the way of cooperation (consider here that European empires are the historical benchmark). And American businesses and innovators are still in the strongest position to work with international peers, so long as The White House allows them to.

And there’s the rub — everything the world is hearing from Trump says that America is closed.

If you liked this article, think about sharing it with anyone who ought to subscribe.